The Guardian is like the Terminator, it absolutely will not stop.

Here’s yet another immigrant’s tale of woe for your entertainment.

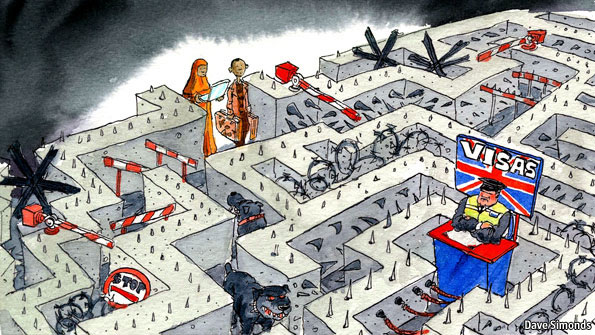

Five years previously, when I had entered the UK on a Writers, Artists and Composers visa I thought the road to settlement, and then citizenship, was flat and paved. As long as I could maintain myself financially, continued to work as a writer, and didn’t break any laws, I’d be eligible for ILR in five years, and citizenship a year later. And then there would be a citizenship ceremony to end it all, which seemed a pleasant enough idea.

So far so good, although I did raise an eyebrow at “which seemed a pleasant enough idea.” A rather curious choice of words to talk about acquiring citizenship, isn’t it? It almost sounds as if she isn’t really taking the concept seriously.

Fancy that.

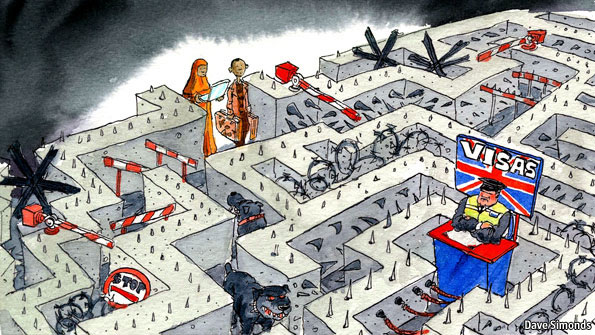

But I wasn’t prepared for the mutable nature of immigration laws, and their ability to make migrants feel perpetually insecure, particularly as the rhetoric around migration mounted.

Weren’t you? Don’t you read the Guardian then?

“I didn’t think that would affect someone like you,” a large number of Brits said to me over the years, with the implacable British belief that if you’re middle class you exist under a separate set of laws. They weren’t entirely wrong – the more privileged you are in terms of income and education the more likely it is you’ll be able to clear all hurdles. It’s only the rich around whose convenience immigration laws are tailored.

And you’re what, shocked and disappointed? Of course a rich, educated immigrant will always be preferable to a poor, illiterate one! You need the skills, tools and social graces that money and education can give you in order to function in a First World country or else you’re wasting everybody’s time, including your own.

Seriously, show me one country in the world which is run as a charity and only takes in waifs and strays. Anyone? Anyone? Bueller?

Soon after my arrival, I had heard of an overhaul of migration laws which would bring in a new “points based” immigration system; but the migration lawyer I spoke to said there was no way that the Writers, Artists and Composers visa could be brought within that system, since there was no way to actually measure “cultural value”. Speaking in a manner that suggested deep insider knowledge, the lawyer said that the migration route I had entered on would remain unchanged. I had enough faith in his polished assurance that I paid little attention when the new points based system was announced.

I’m afraid that lawyer had zero clue about it (how could they?) and therefore told you exactly what you needed to hear – and you believed them because you wanted to. You can’t exactly blame the government for this.

Several months later, near the time when I had to renew my writer’s visa, I went to the UKBA website and discovered my visa category had simply been abolished. I would either have to find some other category for which I was eligible, or leave the country.

I’m flabbergasted. The random lawyer was wrong after all! Say it ain’t so!

Even in all my huge relief, I registered a sense of disappointment at having been transferred from Writers, Artists and Composers to the category Tier 1 (General).

Yes, now you’re just an ordinary member of the public like the rest of us, instead of being an Artiste™. It must burn. It’s almost not worth applying for that pleb visa… oh wait.

Wanna bet this person is a fierce critic of ‘elitism’ the rest of the time?

I never really felt safe after that. Every announcement of proposed changes to migration laws made my heart stutter, every politician’s announcement about slashing migration numbers felt like a threat.

Look, at the end of the day, you have no god-given right to live in London for the rest of your life just because you want to. Half the flipping planet wants to!

You’re not exactly stuffed to the gills with skills the UK desperately needs either. Writers are two a penny. Retrain as a orthopaedic surgeon and we’ll talk.

And so, five years down the line, I was able to apply for ILR – though first I had to take the Life in the UK test, which continues to be mistakenly referred to as a Citizenship Test. At this juncture I received a tremendous outpouring of sympathy from my British friends. “It’s ridiculous,” they said. “Why should you have to learn about the kings and queens of England in order to stay?”

She keeps quoting these mysterious “British friends” who sound too stupid to be allowed. Are they even real?

In fact, the test teaches you little about kings and queens and is full of information about employment rights, schooling, the history of gender equality laws and other rather useful things (though the Tories want to add the kings-and-queens stuff, which will render it absurd.)

No more absurd than the history of gender equality laws. If you don’t know the past, you can’t understand the present.

This kind of knowledge will also allow you not to make a twat of yourself when playing Trivial Pursuit with locals (not your imaginary British friends though, they don’t sound the type).

I had thought dual citizenship would feel like a gain, not a loss. Instead, as I took my seat in the chamber I found myself reflecting on what it means to be from a country in which acquiring a second passport is regarded across the board as reason for celebration. Weeks later, I was trying to explain this to British-Libyan writer, Hisham Matar, who knew exactly what I meant. “In that moment you are betrayed and betrayer both,” he said. “You’re betraying your country by seeking another passport, and you’re betrayed by your country which makes you want to seek another passport”

So many insecurities and chips on both shoulders. Oh dear.

And she’s only got two countries to deal with. How does she think Jason Bourne feels?

What dissipated the feeling of melancholy was a glance toward one end of the council chamber. There was a picture of the Queen in her tiara, set against a large union jack. I might have laughed out loud. It seemed so American: the smiling portrait, all those flags. And then someone pressed “play” on a CD player and classical music filled the room. I want to say it was The Ride of the Valkyries but this seems so over the top that it must be a novelist’s imagination rather than memory. Mustn’t it? All I know is I kept looking across the room at my sister and giggling.

Well, I called it, didn’t I? Getting British citzenship is just a big joke to her, all that matters is that she gets to stay in London.

we all sang – or moved our lips meaninglessly in time to – the national anthem

Oh FFS. Just tear up her certificate and send her back to Pakistan. What a waste of space.

However high my levels of anxiety might have felt along the way, I always knew I had the luxury of another home to return to, as well as a livelihood which wasn’t contingent on being in one place rather than another.

How interesting. What was all that guff about feeling ‘unsafe’ then? Check your privilege, you silly moo!

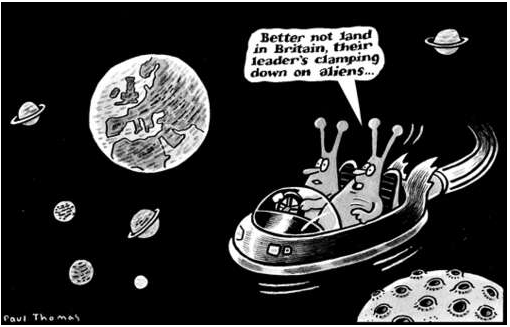

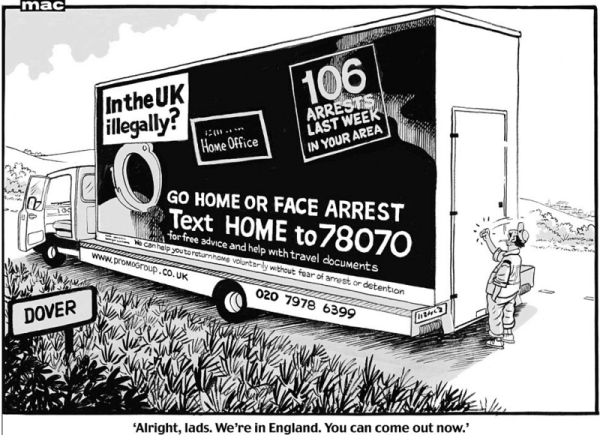

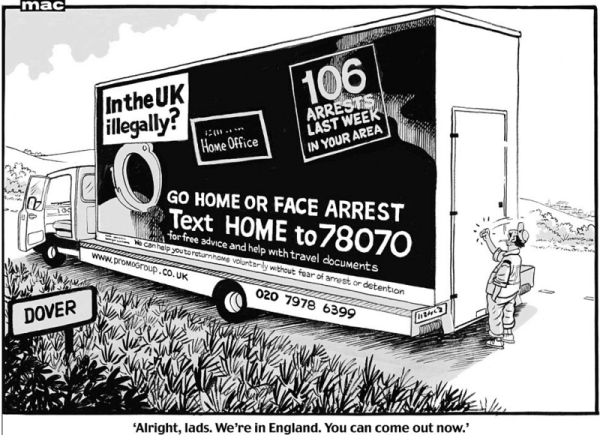

We had all been given envelopes for our certificates, and when I opened mine out popped Theresa May. Or at least a letter of welcome from her, with her photograph at the top of the page. Just a few weeks earlier, May had sent her “Go Home” vans across the UK, so this hardly inspired a feeling of belonging.

ILLEGAL IMMIGRATION.

LEGAL IMMIGRATION.

TWO DIFFERENT THINGS.

is it even necessary to add that the irony here that the resources of the state, as embodied by institutions such as the NHS, would probably collapse without migrants?

But you’re not one of them, are you?

Also: hooray! The legendary “the NHS relies on immigrants” trope makes an appearance! We have a full house!

The first thing I did on returning home was download and fill out a passport application form. Wanting to stay was my primary reason for acquiring citizenship, but the added benefit of a passport that allowed me to travel without the visa nightmares that come attached to a Pakistani passport was also a strong motivating factor.

This says it all. What a worthy addition to the UK this person is. Not.

I filled out the form, took it to the post office, and handed it across the counter to a bearded man with the name tag Khaled.

Khaled, huh? Just like back home!

“First passport?” he asked.

“Yes.”

Khaled looked gravely at me.

“Welcome,” he said, and everything uncomplicated and moving I had wanted to feel in that citizenship ceremony, I felt then.

Oh, now you feel like you belong in the UK. Because Khaled said so. Right.